Back in February, Gagan Biyani of Udemy.com made a terribly poignant assessment of a particular facet of higher education: we are not in the software development business. We are in the knowledge business, and the other functions that take place on campus are ultimately designed around supporting that goal. What I am talking about is flattening. Ultimately, committing entire teams of people to producing and supporting software for the university is a growing burden for us, and it’s my argument that we need to know when to walk away.

To clarify, I understand there will always be specialized software needs at universities - especially in areas related to research that takes place or connecting disparate systems together. What I am talking about are specifically our institutional applications that we all have in common: learning management systems, common application, catalogs, student portals, CRMs, etc. These are areas that in the past, we had no choice but to venture in to on our own. Today, however, vendors can supply many of our most common needs: for a cost.

I don’t expect what I’m going to talk about here to be popular. I don’t expect a lot of people to agree with me either. This is one of those cases where you’re either going to be totally with me, or you’ll think I’ve gone off the deep end. I welcome discussion on the topic, and I know every institution is unique in ways that will make this more true for some, less for others. All I ask is that if you feel the need to lambaste me for what I say today, first consider if the core philosophy of what I’m getting at is flawed, and go after that - I’m already well aware of my personal insanity.

About That Cost

So obviously, cost is indeed a factor. But cost is a factor regardless whether you are purchasing software or paying developers. But because the money comes from different pots, we don’t always think about how they offset. Individually, each school should regularly sit down and audit programming hours versus software costs. Here is an extreme example: which is more cost effective - purchase licenses for 1,000 machines to install Windows, or write your own operating system? We’ll always buy the ready made operating system, because it makes no sense to write our own - heck, we can’t even be bothered to effectively fork a Linux distro for our own needs. I’m not saying buying software is always the answer, but it frequently will be.

And consider this: we already know this is true. Look at the number of schools around the country jumping on board with things like GMail and Google Apps. They’ve discovered that there are huge cost savings in outsourcing these tools. Less administrative maintenance, lower hardware costs, less overall overhead (in people or otherwise), along with better user experience. Google can afford to pour millions of dollars into their email platform to make sure it’s top notch. They employ the best programmersHCI experts, and UI teams. Their security models would run circles around us. How do we stack up to that, by comparison? We can’t compete with those economies of scale, it’s fiscally absurd.

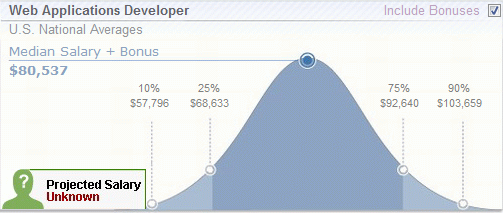

There’s another money issue as well: pay. The fact of the matter is we cannot afford to go after the highest quality or most experienced programmers. We don’t even stand a chance in the open market. Do searches on job boards for higher ed. On average, many universities are paying programmers between $35,000 and $55,000 depending on the position level. Even at the top end of the spectrum, we are miles below the industry standard. In fact, that’s even below the trailing edge of the bell curve.

How does that impact us? Several ways. One, we end up hiring more programmers, because it takes more inexperienced or entry level programmers to do the same amount of work compared to a single really awesome one. Two, we can’t retain the good ones. On the chance we get someone young and eager, they use us (knowingly or not) to get some experience, then jump ship to someone offering way more money once they’ve padded their résumé. The ones we keep around are the ones that can’t go elsewhere (not necessarily because they aren’t talented, but maybe they have ties to the area. Point being, their main reason for being there isn’t because they love the job) or are at the end of their careers. I mean no offense to any of our developer readers, and there are always exceptions, but anecdotally our community is littered with the stories of our friends and colleagues who have moved on to private sector jobs. Where we do need programmers, we’d be much better off competing with the private sector for them and just hire a couple really great ones.

The Higher, the Fewer

So, when we can’t compete with the private sector, we discover that we are trying to create software from subpar resources. In other words, we’ve already set ourselves up for failure. You can tell when you’re in trouble if you ask to look at documentation, or code revisions, or do a security audit. This is something you can actually test out yourself, just go attempt some basic XSS attacks on some of your in house applications (note: it’s probably a good idea to let your security officer know you’re doing this). Try running some accessibility tests, for some extra fun.

Why are those things so frequently issues? Because we aren’t getting the best programmers that also take time to consider things like UI/UX, design, and other factors. Consideration isn’t given to things like APIs. They think in code and code only, and deal with problems only when they come up, rather than planning for them ahead of time. This is ultimately bad for the end product and bad for the user experience.

You’re also likely to notice that higher ed institutions lack any kind of true development shop methodology. You don’t hear words like scrum, agile, or waterfall thrown around when discussing the development of your latest portal system. Commitments to a specific architecture like MVC, MVP, or MVVM are likely to get you quizzical stares. It’s all increasingly problematic at schools that employ multiple programming languages or platforms, as opposed to shops that specialize in one.

If we commit programmers to anything, we should try to focus on using them to create the necessary API interfaces to bind systems together. Work on the mortar, not the bricks.

It’s a Zoo Out There

The other problem we have is that higher ed simply doesn’t know how to treat programming staff. We treat them like animals in a zoo, caged up and limited. If they aren’t stuck in a cubicle farm, they’re walled off in offices or buried in a basement. Either way, silly things like natural light and open communication space isn’t even so much as an afterthought in a lot of places. It’s the kind of place you would stick criminals, not people you want building tools your whole institution would lean on. Use it for storage, not people.

On top of it, while programmers in higher ed tend to get pointed a dozen different directions at any time, in the private sector you usually will find yourself getting into a focused, goal oriented shop - a much better working environment. Good programmers will look for teams that focus on the methodologies they use, or build tools they are familiar with. Bottom line, they find a working environment that fits them like a pair of comfortable shoes.

Think about how the big boys do it. And if not them, think about how even tiny startups do it. Better yet, just think about how any business relying on programmers treats them: don’t hide them, give them room for creative freedom in their space, and give them means to collaborate and communicate (believe it or not, that’s important for everyone, not just programmers). You don’t have to look any farther than the homes of Google, Pixar, Facebook, or Zappos (that’s not to say you have to be worth a billion dollars to give employees a good working environment though, they just happen to excel at it) to see just how they work hard to create an environment that is conducive to work, and also inspiring and designed to keep developers happy. Again, we don’t even compare. That’s no way to attract or retain good employees.

Yeah, but…

I have no doubt the exceptions will chime in with comments to this editorial. And I’m glad they are exceptions. And here’s a good bottom line. If you have talented programmers, and you are paying them enough to keep them there and happy, and they are making software you are proud of that does an awesome job: SELL IT. I’m not even kidding. If you are that lucky, then you need to turn that around and make some money off of it, because you’ve found an equation that would make you capable of competing with the private sector. So milk it, and use the result to give back to the institution.

That’s your barometer. If you would be proud to sell the software that you make in house (customizations not withstanding), pat yourself on the back because you’ve mixed up a batch of the secret sauce. If, however, you give pause to the idea, then maybe - just maybe - your school shouldn’t be in the business at all. Instead, consider a partnership with a development firm that is well versed in addressing customer needs and build a good relationship with them - they know what they’re doing better than any of us could.

Higher ed is one of the few industries that remains hell bent on doing everything ourselves, and for no good reason. More often than not, attachment to these older practices comes out of legacy, rather than good leadership. “It’s always been done that way” is not an excuse that cuts it in today’s market. Even if you’re making it work now, you’re only a turnover or two away from your whole world changing.

Conclusions

End of story: we gotta stop fooling ourselves. This isn’t a world we can win in any longer - heck, we can’t even compete in the first place really. It did make sense once upon a time, but those legacy memories are not a reason to resist doing better. If nothing else, if we aren’t evolving, then the ultimate financial considerations of maintaining internal dev shops will force our hand at a point when we aren’t quite ready for it. We can ease that pain by starting to prepare now.

I don’t want to sound like a negative Nancy, or like an advocate for firing people or downsizing, but change will happen with or without our cooperation. If you aren’t already, questions like these will begin to be asked when it comes to how these efforts best serve our institutional goals, and the answers are getting harder every month that passes.

Photo Credit: ![]()

![]() Some rights reserved by jeantessier

Some rights reserved by jeantessier

By Director of Web Marketing

GeneralProgramming