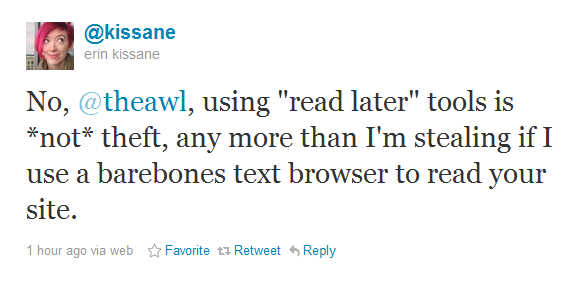

So, I seriously need to stop talking to people on Twitter. First the QR code debate, now this. The issue in question was started by a post over at The Awl discussing if “read later” tools are theft. The theory being that third parties are effectively stealing the content of other sites when they allow users to read the sites’ content out of band. The connecting tissue came from a tweet by the frequently colorful Erin Kissane:

Before I go into anything else, I want to make it clear that I do not disagree with Erin philosophically. I use Instapaper. I love Instapaper. The issue comes down to where it falls legally. In that regard, I fear that if challenged in a courtroom, Instapaper - and others like Pulse.me, Readability, or Evernote - would lose. And that’s not ultimately a good thing. This is why I’ve been so big on promoting Creative Commons, because it helps clear up issues that have been created by digital content in a country that has such abused and broken copyright law. It isn’t a perfect solution, but it is a better one. Disclamer: I am not a lawyer, but I play one on TV.

Metaphorically Speaking

I think the best way to start would be to build on an extended metaphor. Imagine your personal blog is like an independent art gallery. You paint pretty paintings (not like that hack Jackson Pollock). You show them. You have decided anyone can come into your gallery and look at your works. Heck, they could sit there staring at one painting for forty-seven hours if they wanted, and you wouldn’t fuss. But, as a condition for viewing your content, they visitor had to agree not to photograph anything. After all, this is your gallery and your hard work. You’ve been kind enough to let them come in and consume it all they want while they are there, but if they want to take some home with them to study later, you’d prefer they buy one of the poster copies in the corner. That is your prerogative, and your right under copyright law. The artist next door may not care, he let’s people look at - and even borrow - the things that he creates. That too is up to him. This is a similar problem with the idea of read later.

This sets up the scenario for those that prop up the RSS position. Some argue that since many sites offer up full text RSS feeds (occasionally ad-free, as well), they are ceding ground to those that would consume their content anywhere. This is certainly legal gray area that has yet to be defined by case law. The caution I would issue is that using an RSS feed is not necessarily the same as scraping the site itself for content. Like the example above, I have the choice to issue an RSS feed. I have the choice to make it an excerpt, or full-text. And, one could argue, I have the right to set expectations on how that is consumed. Yes, you can do many things with an RSS feed, technologically speaking, but that doesn’t preclude the content creator putting stipulations on that usage.

It’s the same reason why things like DRM aren’t illegal. DRM is used to extend the rights of a copyright holder to better reflect the control they want to exert over their creations. Technology has enabled content producers to realize controls they couldn’t before. We aren’t there with RSS yet, just like we weren’t there with eBooks for a long time. But all that takes is time. So to argue that a producer’s inability to control their RSS feed is tantamount to a blessing of “use my content however you want” is not a defense against the argument that ultimately they do possess the right to do so - in the end, some day the tools will match the dream. The only caution is when the technology gets in the way of - or prevents outright - legitimate fair use (we’ll discuss that in a bit). It’s important technology enable positive controls on licensing and rights, and not be used to lock things down just because.

Consumption Shifting

The idea of consumption shifting is defined by the process whereby a consumer is able to either time or space-shift content for use outside of it’s original presentation. There are a lot of comparisons that get thrown around when debating this issues. For example, we can time and/or space-shift things on TV using DVRs and VCRs (ancient machines that recorded audio and video onto magnetic tape reels). We’ve been allowed to do it for ages, and courts have upheld the right. So, why shouldn’t we be able to do the same with web content? The counterpoint is delivery. Broadcast airwaves are considered public property. That’s why you can put up some bunny ears (no, not the sexy kind) and get a half dozen free channels. As such, you have a limited right to time and space shift that content all you want because you’re a tax paying citizen. But downloading a torrent of the latest episode of Dexter when you haven’t paid for Showtime? Guess what that is? Theft. If you pay for cable, it is understood that it comes with the privilege of shifting that content for later consumption, like filling a bucket of water for use later or somewhere else. Same goes for clipping a newspaper or magazine you get. Try that at a bookstore though: “Hey, I appreciate you letting me read some of this in your store. I can’t finish it now, so I’m gonna just take this page home with me to re- hey… why are you chasing me?”

But we pay for internet access, right? Yes, but that’s not the same at all, because none of what you spend is used to compensate content creators, only the service provider. At least in theory, part of what you pay for things like cable ultimately benefit the people making what you watch, as part of the agreement between them and the cable company, and then the cable company and you. This is where Readability is hoping to make a dent, by offering a way to compensate content creators for allowing people to shift their content. It’s novel and noble. They even hold payments for a year, so if you’re just hearing about it, you can claim your domain and get payments from the past year of viewing.

In the tweet above, Erin compares using Instapaper to reading a website in Lynx. Unfortunately, that’s more of a red herring than a justification since it can’t really be considered space-shifting. The debate isn’t about reading content in “plain text,” but rather software companies have the right to repurpose someone’s content for presentation. Usage of Lynx is, realistically, little more than a novelty in today’s web any, and is just a reflection of how the medium has changed to better enable monetization of content (and you know, all those other advances we’ve made in web presentation since 1992). Not to mention that Lynx still does not preclude an author from attempting to derive revenue from something you want to view on their website, it’s just a matter of if it is worth it to go through that effort. In the next section I’ll talk about why just the possibility of a market is justification for defending a copyright, even if the creator isn’t actively making money on something. (Fun fact, Lynx is still actively maintained by Thomas Dickey. The 2.8.8 development release came out in January.)

Understanding Fair Use

Of course, being in higher ed, at some point you will hear a professor talk about how using something in the classroom is fair use. The same is often argued in the debate of reading a page elsewhere. After all, limited home, non-commercial usage of your time-shifted recorded television shows is fair use. The problem is, in many instances, that simply isn’t the case. The extent to which this is a problem varies greatly, and ultimately, the only way to know what qualifies as fair use is to go through the following litmus test that a court would use. That test involves weighing four factors:

- the purpose and character of your use

- the nature of the copyrighted work

- the amount and substantiality of the portion taken, and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market.

The final check is the one that really could be the problem in the case of services like Instapaper. As the Stanford page above discusses:

“Depriving a copyright owner of income is very likely to trigger a lawsuit. This is true even if you are not competing directly with the original work.”

This is certainly an issue for sites behind a paywall, but many sites just rely on advertising income (or try to) generated by viewing the content. By removing that context, companies are directly impacting income for the author. Even sites that don’t have advertising can argue that such use infringes, because there is a potential market. Whether you like that or not, it’s an issue a court would take into account, and more often than not, they side with the creator. And keep in mind, simply crediting the source is not necessarily sufficient.

Odds are, if it’s just you printing a page, or event copy/pasting text into Evernote yourself, that would probably end up falling under fair use as “home, non-commercial use.” This becomes a problem particularly in cases like Instapaper or Evernote, that are attempting to create a revenue stream based on the abilities they enable. Readability can argue that they are trying to compensate creators all they want, but in the end, legally speaking, they are infringing on the market without license. That doesn’t make them evil, mind you. In fact, Readability is working towards the greater good (or so I like to hope) - a fact that could play into their favor with a judge. But it’s still more gray than black and white. The question comes down to this: Is Instapaper a VCR, or are they a greedy entity trying to profit on others’ work? I don’t have an answer.

Why CC Matters

So, this brings me back to my point. If you aren’t, please take the time to put a Creative Commons license on things you create. Flickr has allowed this for ages. YouTube just started. You can put one on your own blog (we do here, as you can see below). Why? To protect yourself and make it clear to others what you will permit. It’s not perfect, but it’s a good start that helps bring definition to some of the questions on copyright in the digital world. Better still, getting in to Creative Commons will encourage you to educate yourself about just what is and is not allowed under copyright. Part of the problem in this matter is the amount of ignorance still prevalent with respect to just how copyright works. More to the point, you’ll begin to learn just how screwed up things are, and maybe work to help fix it.

You know what comes next. Share your thoughts below. Do you see things differently? Why? In the end, despite my interpretation of how the law would play out in court, I mentioned that philosophically I agree that it shouldn’t be an issue moving content around for consumption. Ultimately, I’m a strong believer that knowledge and content ultimately want to live freely and they do best when you enable them to move fluidly. But when has law ever made things simpler and logical?

Photo credit: ![]() Some rights reserved by Horia Varlan

Some rights reserved by Horia Varlan

By Director of Web Marketing

copyrightGeneral